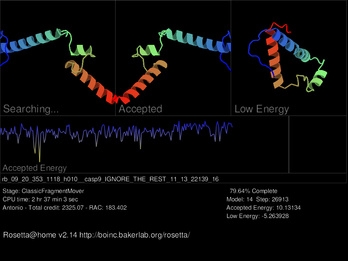

Rosetta@Home screen saver

Rosetta@Home screen saver The next time you get into an argument with your laptop or shake a fist at your computer, try to refrain from calling it “a stupid machine.” That would be gloating. We really are more intelligent than our computers. Case in point, the human mind can solve puzzles better than computers. On this principle, using game elements in citizen science, called gamification, is a popular approach in biology. That's the topic of the next #CitSciChat on Twitter.

The next time you want to argue against a group, think twice. Groups can be more intelligent than individuals. On this principle, some game elements often involve creating teams that compete against each other. Within group cooperation, in the context of competition across teams, is a powerful motivator.

The fields gamified in citizen science - molecular, cell, and synthetic biology - are key to understanding, treating, and curing diseases. Studies of proteins, amino acids, RNA, and DNA can happen in silico (in computer models) and in vitro (in laboratory experiments), but are often too difficult in vivo (in a living cell). Now these serious topics of research are being carried out in gamo. (have I coined a term, in Latin no less?)

For example, figuring out DNA configurations presented researchers with problems that were computationally too intensive for a single computer. At first, molecular biologists looked for a solution with a type of citizen science called distributed computing. Volunteers help research by donating their unused CPU (Central Processing Unit) and GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) cycles on their personal computers to causes like Rosetta@Home and Folding@Home.

Unexpectedly, when distributed computing volunteers saw the screensaver of Rosetta@Home, as it illustrated the computer stepping closer and closer to a solution of each protein-folding puzzle, they wanted to guide the computer. Volunteers came to the conclusion that they could solve these 3-D puzzles better than their computers. Researchers and game designers believed in the abilities of their volunteers and declared, “Game on.”

At the cellular level, human minds are important again. One doesn’t have to be a trained pathologist to identify cancer cells and help find biomarkers in these cells. Cancer Research UK takes games very seriously. In their newest game, Reverse the Odds, players identify bladder cancer cells before and after different treatments, which will help future patients know whether their best odds are with surgery or chemotherapy.

Why are people better than computers at protein-folding puzzles? Why is the human mind better than computer algorithms at figuring out how DNA regions align? Why is the trial and error approach of people better than formal techniques and alogrithms of bioengineering RNA? Why are teams smarter than individuals? Why is gamification so popular that, when the online game Phylo launched in 2010, the computer servers crashed, unable to handle the volume of thousands of simultaneous players? Why are there over 37,000 people working (meaning playing) at RNA design puzzle in an open, online laboratory called EteRNA?

For answers to these questions and more, join us for the next citizen science Twitter chat by following the hashtag #CitSciChat. The #CitSciChat are co-sponsored by SciStarter and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Anyone is welcome to join with questions, answers, comments, and ideas. Don’t be shy and don’t forget to include the hashtag #CitSciChat so that others in the conversation don’t miss your Tweets. I will Storify each session and post the recap on this blog.

The #CitSciChat guest panelists this Wednesday, February 25 at 7pm GMT (26th in Australia) include:

Phylo, nanocrafter and FoldIt were featured in a recent SciStarter newsletter, check out the rest of the projects here and sign up for the newsletter on the SciStarter homepage to get to know about more.

Citizen science chats take place on Twitter at #CitSciChat the last Wednesday (Thursday in Australia) of every month, unless otherwise noted. To involve people across the globe, chats take place 7-8pm GMT, which is 2-3pm ET in USA and Thursday 6-7am ET in Australia. Each session will focus on a different theme. To suggest a project or theme for an upcoming chat, send me a tweet @CoopSciScoop!

The next time you want to argue against a group, think twice. Groups can be more intelligent than individuals. On this principle, some game elements often involve creating teams that compete against each other. Within group cooperation, in the context of competition across teams, is a powerful motivator.

The fields gamified in citizen science - molecular, cell, and synthetic biology - are key to understanding, treating, and curing diseases. Studies of proteins, amino acids, RNA, and DNA can happen in silico (in computer models) and in vitro (in laboratory experiments), but are often too difficult in vivo (in a living cell). Now these serious topics of research are being carried out in gamo. (have I coined a term, in Latin no less?)

For example, figuring out DNA configurations presented researchers with problems that were computationally too intensive for a single computer. At first, molecular biologists looked for a solution with a type of citizen science called distributed computing. Volunteers help research by donating their unused CPU (Central Processing Unit) and GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) cycles on their personal computers to causes like Rosetta@Home and Folding@Home.

Unexpectedly, when distributed computing volunteers saw the screensaver of Rosetta@Home, as it illustrated the computer stepping closer and closer to a solution of each protein-folding puzzle, they wanted to guide the computer. Volunteers came to the conclusion that they could solve these 3-D puzzles better than their computers. Researchers and game designers believed in the abilities of their volunteers and declared, “Game on.”

At the cellular level, human minds are important again. One doesn’t have to be a trained pathologist to identify cancer cells and help find biomarkers in these cells. Cancer Research UK takes games very seriously. In their newest game, Reverse the Odds, players identify bladder cancer cells before and after different treatments, which will help future patients know whether their best odds are with surgery or chemotherapy.

Why are people better than computers at protein-folding puzzles? Why is the human mind better than computer algorithms at figuring out how DNA regions align? Why is the trial and error approach of people better than formal techniques and alogrithms of bioengineering RNA? Why are teams smarter than individuals? Why is gamification so popular that, when the online game Phylo launched in 2010, the computer servers crashed, unable to handle the volume of thousands of simultaneous players? Why are there over 37,000 people working (meaning playing) at RNA design puzzle in an open, online laboratory called EteRNA?

For answers to these questions and more, join us for the next citizen science Twitter chat by following the hashtag #CitSciChat. The #CitSciChat are co-sponsored by SciStarter and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Anyone is welcome to join with questions, answers, comments, and ideas. Don’t be shy and don’t forget to include the hashtag #CitSciChat so that others in the conversation don’t miss your Tweets. I will Storify each session and post the recap on this blog.

The #CitSciChat guest panelists this Wednesday, February 25 at 7pm GMT (26th in Australia) include:

- Seth Cooper (@UWGameScience) at University of Washington, with Foldit and nanocrafter

- Jerome Waldispuhl (@PhyloDNApuzzles) at McGill University, with Phylo

- Benjamin Keep (@bkeep) at Stanford, with EteRNA,

- Leslie Harris @LittleVenetian at Cancer Research UK (@CR_UK), with Reverse the Odds

- Vickie Curtis (@Vickie_Curtis), who received her PhD at Open University where she investigated gamification in citizen science. Next week she begins with the Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology at the University of Glasgow.

- Paul Gardner (@ppgardne), at University of Canterbury, New Zealand, Editor for RNA Biology & PLOS Computational Biology

Phylo, nanocrafter and FoldIt were featured in a recent SciStarter newsletter, check out the rest of the projects here and sign up for the newsletter on the SciStarter homepage to get to know about more.

Citizen science chats take place on Twitter at #CitSciChat the last Wednesday (Thursday in Australia) of every month, unless otherwise noted. To involve people across the globe, chats take place 7-8pm GMT, which is 2-3pm ET in USA and Thursday 6-7am ET in Australia. Each session will focus on a different theme. To suggest a project or theme for an upcoming chat, send me a tweet @CoopSciScoop!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed